Wednesday, April 29, 2009

Final Post...maybe?

So, we come to the end, heh? School is like Christmas--you never remember what you were given then in July. So, the most important question to ask (of any class) is what have I learned? Nothing, is the correct answer. Aside from learning the dynamics of orality, I have learned that it is possible to understand the universe inside myself. We realized these possibilites with our memory theater, but I truly enjoy entertaining the idea that I can know everything if I put my mind to it. More importantly, I've enjoyed seeing this possibility materialize in each of you. There is always something bigger in Dr. Sexson's classes. Often, the overarching theme is making the ordinary extraordinary (which no doubt can be applied to this class, and has been through Groundhog's Day), but for this class, it seems that we can make ourselves extraordinary by interorizing the outside world of both orality and textuality. "If you want to bake an apple pie from scratch, you must first recreate the universe" (Carl Sagan), and this is what seems to have taken place in this class, with Shaman as Pastry Chef. To understand the universe, we have created within ourselves the universe.

Wednesday, April 22, 2009

My Presentation

An applehead bahlness wearing a tow sack with schtriwwelich hair was gretzing about dippy ecks. So I tolls her, madam, I’ll switcher yer a polecat fer dem dippy ecks, if I getsuh bulbenik wid it. She certainly was schmegegge. She said her hoonanny was in buck pasture, but it aint why she was a moldoon . From these few short sentences it is not difficult to ascertain how the typographic mode of communication has also lent itself to a collective, yet unconscious, sense of alienation. I am too far steeped in my own decadent generation to fully engender primary orality within myself, but from my campfire experiences and time spent with my dogs I might be able to assume some of those underlying premonitions that might be felt if you were to place a being of oral antiquity in a visually illuminated and defined world such as our own. All semblance of niche united knowledge—gone. The tiniest expression or nuance or individual thought—not to be found. The chances of phonetically communicating in such a way that everyone around can understand—slim. Yet the urgency to correctness and conformity will heavily impose themselves on this wayward traveler as not only does typographic space demand staunch coherency (especially if nationalism is to prevail) to its rigid, grammatical formulations, but that space becomes so expansive and specialized that it becomes impossible for this oral alien to experience the cultural tradition as a patterned whole.

To first understand how expansive print has made the [American] cultural repertoire, simply walk into your nearest bookstore. There is, upon immediate entrance, an overwhelmingly vast amount of material to read in too little time that one cannot feel, as he reaches his life’s decrescendo, that he has learned or experienced all that was available to him. This scenario is entirely the opposite of an oral era where “every social situation cannot but bring the individual into contact with the groups’ patterns of thought, feeling and action: the choice is between the cultural tradition—or solitude” (Goody, 59). What has become so decadent and lamentable about my generation is the immediate gratification and the infinite amounts of personal selection available to a young boy or a girl. If Tiny Tim does not want to be a laborer he can go to school and learn another trade that, although lacking the social utility that a tight-knit, patterned oral community would necessitate, might earn him far greater riches and joys in life. The advent of print, and its production of textbooks from which Tim can study, enabled these choices. If Dainty Daisy decides she wants to study the pooping patterns of ungulates west of the Great Divide where the regional air quality is dense with Legionella, she may also specialize in this field. Yet this notion of specialization is fundamentally at odds with those of daily life, common knowledge, and an oral culture’s need immediate social utility. This conflict, teases Jack Goody, “is embodied in the long tradition of jokes about absent-minded professors” (Goody, 60).

Professors, though, are not the only ones who forget. Due to the size and unchecked propagation of the literate gamut, the amount of information that relates to a cultural, patterned whole that any one present-day individual knows must be miniscule in comparison with our Wayward Oral Alien. His culture is homeostatic whereby an equilibrium is achieved by “sloughing off memories which no longer have present relevance” (Ong, 46). Print’s sheer producing and recording power has with it no system of elimination, and produces what Goody describes as “structural amnesia” which “prevents the individual from participating fully in the total cultural tradition to anything like the extent possible in non-literate society” (Goody, 57). Consequently, this system fosters a strong sense of alienation from one’s own culture. Nietzsche himself felt alienated after attempting to converse with Tiny Tim and Dainty Daisy, but resorted to small talk and calling them “Walking Encyclopedias” after realizing that, because of print, they were bratty, know-it-all, undergrads.

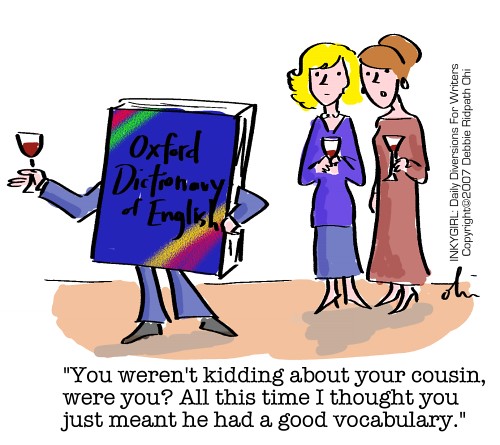

Encyclopedias and Dictionaries epitomize this accumulation of knowledge found in modern, literate persons. The enormous lexicon of information and vocabularies produced within the endpapers of these printed behemoths—the 1909 edition of Webster’s New World Dictionary contains over 400,000 entries—comprises what Einar Haguen termed and Walter Ong describes as the “Grapholect.” The written language of the grapholect arises from dialects—varieties of a language that are characteristic of a particular group of the language’s speakers. Though the United States does not have an official language, our grapholect is distinctly [North] American and from it a standardized, national language has emerged. The modern grapholect reestablishes connectedness throughout a nation once divided by various oral speech forms. Ong asserts that because all other English dialects are interpreted in the grapholect, that “those competent in the grapholect today can establish easy contact not only with millions of other persons but also with the thought of centuries past...”(Ong, 106).

This all speaks well and fine of a literate person today, but what of an illiterate person living in such a highly textual environment, or simply someone not as well-versed in the grapholect? Though Father Ong seems relatively optimistic about the emergence of the grapholect, Marshall McLuhan seems less than willing to accept print as a tool of human progress and emancipation while quoting Harold Innis’s The Bias of Communication. “Application of power to communication industries hastened the consolidation of vernaculars, the rise of nationalism, revolution, and new outbreaks of savagery in the twentieth century” (Marshall McLuhan, 216). The consolidation of unique vernaculars into the dictionary which is to be our principal typographically communicative source creates “special classes of readers with little prospect of communication between them” (McLuhan, 216). Sadly, the dialects that have given our grapholect character, as well as those pockets of America that continue to use them, have been ousted, marginalized and are subject to constant complaints of “Grammar Nazis”.

Jack Goody brilliantly states that, unlike in an oral culture when the decision is either cultural tradition or solitude, “the mere fact that reading and writing are normally solitary activities means that in so far as the dominant cultural tradition is a literate one, it is very easy to avoid...” (Goody, 60). Thus, from a literate culture arises a new type of alienated man—the Byronic Hero who marches to the beat of his own drum, shuns appearances and the edicts of the unwashed, consumer-oriented society, and sounds his own dialect and “barbaric yawp”. McLuhan describes these Whitmanian characters as not only marginal, but also as oral and as having great appeal to the new, visually oriented literate crowd. “For the marginal man is a centre-without-a-margin, an integral independent type...The new urban or bourgeois man is centre-margin oriented. That is, he is visual, concerned about appearances and conformity or respectability” (McLuhan, 213). These qualities of marginality, orality, unrestraint, and adherence to nonstandard, and therefore quite possibly magical and certainly intriguing, vernaculars make, for the small collection of other washed and marginal characters who allow negative capabilities, artists such as Faulkner and Joyce a pleasure to read.

The new urban image is all about glamour and it has permeated our culture through every possible agency, as witnessed when perusing magazine stands or channel surfing. This commercialized ideal of glamour and the overarching importance of appearances take root in the literate instigation of grammar. In a world dictated by appearances, the need (as Kris of the Laughing Rats has demonstrated) for conformity, correctness, and an observable sense of Nationalism, makes it is hopeless for literates to live “without dictionaries, written grammar rules, punctuation, and all the rest of the apparatus that makes words into something you can “look” up...” (Ong, 14). Wayward Oral Alien is attempting, but unable, to decipher the sound two dots held in vertical alignment makes, to communicate the gutturalness of a line that tapers to a dot, to voice the agitation of a dot held over a dot with a tail or resonate the hesitancy of a squiggly dot, ampersand or an ellipses. “It is presumably impossible to make a grammatical error in a non-literate society, for nobody ever heard one” (McLuhan, 239). When the ink is firmly stamped and set, that which makes Mongolian Throat Singers spellbinding and a little flyting or stichomythia so scathing subordinates what is readily apprehend by the reader on the page, only to be imagined somewhere between the lines; and the second, intoned language that accompanies dialect and grapholect alike is relinquished to the realm of appearances, all true meaning lost.

Print permanently altered the conscious and unconscious realities of the literate individual since the invention of the printing press in 1440; until just recently, in an era of unrelenting, global, electronic stimulation, are we beginning to think on a more oral, socially intuit level—but only after we have disregarded spontaneity and succumbed to heavy introspection. We become more globally up-to-date through the urgings of textual media, more socially aware because that is every citizen’s responsibility according to the book. First we turn inward to the solitude of literature and print, which then tells us to turn outward to our community. It is this first step which Wayward Oral Alien and all marginal characters find unnecessary.

To first understand how expansive print has made the [American] cultural repertoire, simply walk into your nearest bookstore. There is, upon immediate entrance, an overwhelmingly vast amount of material to read in too little time that one cannot feel, as he reaches his life’s decrescendo, that he has learned or experienced all that was available to him. This scenario is entirely the opposite of an oral era where “every social situation cannot but bring the individual into contact with the groups’ patterns of thought, feeling and action: the choice is between the cultural tradition—or solitude” (Goody, 59). What has become so decadent and lamentable about my generation is the immediate gratification and the infinite amounts of personal selection available to a young boy or a girl. If Tiny Tim does not want to be a laborer he can go to school and learn another trade that, although lacking the social utility that a tight-knit, patterned oral community would necessitate, might earn him far greater riches and joys in life. The advent of print, and its production of textbooks from which Tim can study, enabled these choices. If Dainty Daisy decides she wants to study the pooping patterns of ungulates west of the Great Divide where the regional air quality is dense with Legionella, she may also specialize in this field. Yet this notion of specialization is fundamentally at odds with those of daily life, common knowledge, and an oral culture’s need immediate social utility. This conflict, teases Jack Goody, “is embodied in the long tradition of jokes about absent-minded professors” (Goody, 60).

Professors, though, are not the only ones who forget. Due to the size and unchecked propagation of the literate gamut, the amount of information that relates to a cultural, patterned whole that any one present-day individual knows must be miniscule in comparison with our Wayward Oral Alien. His culture is homeostatic whereby an equilibrium is achieved by “sloughing off memories which no longer have present relevance” (Ong, 46). Print’s sheer producing and recording power has with it no system of elimination, and produces what Goody describes as “structural amnesia” which “prevents the individual from participating fully in the total cultural tradition to anything like the extent possible in non-literate society” (Goody, 57). Consequently, this system fosters a strong sense of alienation from one’s own culture. Nietzsche himself felt alienated after attempting to converse with Tiny Tim and Dainty Daisy, but resorted to small talk and calling them “Walking Encyclopedias” after realizing that, because of print, they were bratty, know-it-all, undergrads.

Encyclopedias and Dictionaries epitomize this accumulation of knowledge found in modern, literate persons. The enormous lexicon of information and vocabularies produced within the endpapers of these printed behemoths—the 1909 edition of Webster’s New World Dictionary contains over 400,000 entries—comprises what Einar Haguen termed and Walter Ong describes as the “Grapholect.” The written language of the grapholect arises from dialects—varieties of a language that are characteristic of a particular group of the language’s speakers. Though the United States does not have an official language, our grapholect is distinctly [North] American and from it a standardized, national language has emerged. The modern grapholect reestablishes connectedness throughout a nation once divided by various oral speech forms. Ong asserts that because all other English dialects are interpreted in the grapholect, that “those competent in the grapholect today can establish easy contact not only with millions of other persons but also with the thought of centuries past...”(Ong, 106).

This all speaks well and fine of a literate person today, but what of an illiterate person living in such a highly textual environment, or simply someone not as well-versed in the grapholect? Though Father Ong seems relatively optimistic about the emergence of the grapholect, Marshall McLuhan seems less than willing to accept print as a tool of human progress and emancipation while quoting Harold Innis’s The Bias of Communication. “Application of power to communication industries hastened the consolidation of vernaculars, the rise of nationalism, revolution, and new outbreaks of savagery in the twentieth century” (Marshall McLuhan, 216). The consolidation of unique vernaculars into the dictionary which is to be our principal typographically communicative source creates “special classes of readers with little prospect of communication between them” (McLuhan, 216). Sadly, the dialects that have given our grapholect character, as well as those pockets of America that continue to use them, have been ousted, marginalized and are subject to constant complaints of “Grammar Nazis”.

Jack Goody brilliantly states that, unlike in an oral culture when the decision is either cultural tradition or solitude, “the mere fact that reading and writing are normally solitary activities means that in so far as the dominant cultural tradition is a literate one, it is very easy to avoid...” (Goody, 60). Thus, from a literate culture arises a new type of alienated man—the Byronic Hero who marches to the beat of his own drum, shuns appearances and the edicts of the unwashed, consumer-oriented society, and sounds his own dialect and “barbaric yawp”. McLuhan describes these Whitmanian characters as not only marginal, but also as oral and as having great appeal to the new, visually oriented literate crowd. “For the marginal man is a centre-without-a-margin, an integral independent type...The new urban or bourgeois man is centre-margin oriented. That is, he is visual, concerned about appearances and conformity or respectability” (McLuhan, 213). These qualities of marginality, orality, unrestraint, and adherence to nonstandard, and therefore quite possibly magical and certainly intriguing, vernaculars make, for the small collection of other washed and marginal characters who allow negative capabilities, artists such as Faulkner and Joyce a pleasure to read.

The new urban image is all about glamour and it has permeated our culture through every possible agency, as witnessed when perusing magazine stands or channel surfing. This commercialized ideal of glamour and the overarching importance of appearances take root in the literate instigation of grammar. In a world dictated by appearances, the need (as Kris of the Laughing Rats has demonstrated) for conformity, correctness, and an observable sense of Nationalism, makes it is hopeless for literates to live “without dictionaries, written grammar rules, punctuation, and all the rest of the apparatus that makes words into something you can “look” up...” (Ong, 14). Wayward Oral Alien is attempting, but unable, to decipher the sound two dots held in vertical alignment makes, to communicate the gutturalness of a line that tapers to a dot, to voice the agitation of a dot held over a dot with a tail or resonate the hesitancy of a squiggly dot, ampersand or an ellipses. “It is presumably impossible to make a grammatical error in a non-literate society, for nobody ever heard one” (McLuhan, 239). When the ink is firmly stamped and set, that which makes Mongolian Throat Singers spellbinding and a little flyting or stichomythia so scathing subordinates what is readily apprehend by the reader on the page, only to be imagined somewhere between the lines; and the second, intoned language that accompanies dialect and grapholect alike is relinquished to the realm of appearances, all true meaning lost.

Print permanently altered the conscious and unconscious realities of the literate individual since the invention of the printing press in 1440; until just recently, in an era of unrelenting, global, electronic stimulation, are we beginning to think on a more oral, socially intuit level—but only after we have disregarded spontaneity and succumbed to heavy introspection. We become more globally up-to-date through the urgings of textual media, more socially aware because that is every citizen’s responsibility according to the book. First we turn inward to the solitude of literature and print, which then tells us to turn outward to our community. It is this first step which Wayward Oral Alien and all marginal characters find unnecessary.

Friday, April 17, 2009

A Blog for Lynda Sexson

Hi everybody. This blog is more or less intended for Lynda Sexson in relation to an assignment for our "Text and Image" class. It is Carl Sagan relating the murder of Hypatia to the loss of the Library of Alexandria. We may understand his point in relation to our class by seeing Hypatia as Giordano Bruno, or someone who tries to understand infinity but is killed for it. This clip is from Cosmos. I watched an hour of this series last night and within the first 5 minutes Sagan had demonstrated the "mis-en-abyme" idea by holding a mirror on each side of a candle, explaining that there is an "infinite regress" in the infinites of the very small and very large. I see Carl Sagan as being very kindred to the like of the people we have been studying, such as Joyce or Lull or many other writers the Dr. Sexson(s) would deem as "good", in the sense that they do not limit themselves only to what they can see or readily attain in the world but constantly seek other-worldly and even God-like wisdom, always tring to incorporate infinity.

Thursday, April 16, 2009

A concise explanation of our presentation

Our group used "Maps" as a jumping off place for our ideas. Because we didn't have much time, we all decided to write our own little stories within the context of a larger one, hence invoking the idea of frames. Numerous allusions to texts such as F.W., Ozymandius, and the Divine Comedy were made to also enhance the mis-en-abyme effect of our story. We did not know what the other stories were prior to reading them, but if they had not fit together that would have been fine because so many of the myths in Kane jump from place to place that you start to get the idea that theme connects the events rather than cause and effect. We told the story of a man who had been drunk the previous night and was in search of a book he had lost. The only hitch was that he had no literate means of re-tracing his steps. We figured that an inebriated individual was the closest thing to a primary orality we could effectively and believably write and personify (except for maybe a dog), yet there is still some "residual textuality" left in our story and in the perceptions of our protagonist. The biggest qualm that anyone has, including Plato, is that we cannot express oral perceptions in a textual way.

So off went our adventurer retracing his steps, using everything un-texual to find where he was going. In this way we were easily able to use Kane, who explained that oral myths were rooted in the land, and that "what holds the whole elaborate structure of stories fresh in memory is the likeness of the patterns of story to the life of the land." As such, we also wanted you as a class to use the "lay-of-the-land" to try to determine where we are going. Each place on our route was, as Kane would describe, a "place of local meaning where mystery is felt". Because myths use maps, but not of the chirographic kind, it would seem that one must incorporate elements of synesthesia into his or her natural way of life. You need to develop different sensory ways of perceiving the same material.

The route went as such: Library, Spectators, Stadium, Montana Hall, Duck Pond, Cooper Park, The Barmuda Triangle, Pita Pit, the "M", Bozeman Beach, GV Mall, and back to Renne Library. I'm am positive that there were things I didn't catch in our story, but each locale had a certain association, or maybe mnemonic device, which made the map like a memory theater. Jose Arcadio Buendia's suicide smelt like the gun powder they use to blast off the cannon when the Cats score a touchdown, MT Hall is where the moocow was led but unable to walk down. I think one of the larger themes that we tried to exemplify was a way of telling a story, understanding history, and organizing ideas through agencies other than text, because, it would seem, once text gets involved in these processes the possibility of their manifestation has "gone to shit". There is no socially coherent way of mapping (the origins, limitations, mores, etc.) a community when typography makes that community expansive and global. But, when we use non-textual devices to try to describe where we are in Bozeman, it becomes something known only to locals, it becomes esoteric.

I'm going to end there. So much for conciseness. Read Melissa, Robert, Karrie (sp*, sorry), and Parker's blog because I am sure they had different ideas about our objective, but nonetheless they presented wonderful versions of the whole that surprised and entertained me as much as you (I hope).

So off went our adventurer retracing his steps, using everything un-texual to find where he was going. In this way we were easily able to use Kane, who explained that oral myths were rooted in the land, and that "what holds the whole elaborate structure of stories fresh in memory is the likeness of the patterns of story to the life of the land." As such, we also wanted you as a class to use the "lay-of-the-land" to try to determine where we are going. Each place on our route was, as Kane would describe, a "place of local meaning where mystery is felt". Because myths use maps, but not of the chirographic kind, it would seem that one must incorporate elements of synesthesia into his or her natural way of life. You need to develop different sensory ways of perceiving the same material.

The route went as such: Library, Spectators, Stadium, Montana Hall, Duck Pond, Cooper Park, The Barmuda Triangle, Pita Pit, the "M", Bozeman Beach, GV Mall, and back to Renne Library. I'm am positive that there were things I didn't catch in our story, but each locale had a certain association, or maybe mnemonic device, which made the map like a memory theater. Jose Arcadio Buendia's suicide smelt like the gun powder they use to blast off the cannon when the Cats score a touchdown, MT Hall is where the moocow was led but unable to walk down. I think one of the larger themes that we tried to exemplify was a way of telling a story, understanding history, and organizing ideas through agencies other than text, because, it would seem, once text gets involved in these processes the possibility of their manifestation has "gone to shit". There is no socially coherent way of mapping (the origins, limitations, mores, etc.) a community when typography makes that community expansive and global. But, when we use non-textual devices to try to describe where we are in Bozeman, it becomes something known only to locals, it becomes esoteric.

I'm going to end there. So much for conciseness. Read Melissa, Robert, Karrie (sp*, sorry), and Parker's blog because I am sure they had different ideas about our objective, but nonetheless they presented wonderful versions of the whole that surprised and entertained me as much as you (I hope).

Monday, April 6, 2009

Class test questions...explicated

Hi everybody. We all have the same notes for class (I copy and pasted these from Chris's blog, so thanks), but I thought I'd expand on them just a bit. Not that any of the expansion will be on the test, but it might help to jog your memory if we can make a few connections and get past the esoterica of abstractions. One question I would have like to have seen is "If you want somebody to grow up to be a thief you call them a.....thief! A question that represents the power of suggestion in either a primarily oral or a literate culture--or a secondarily oral culture.

1. Nietzsche says we are all walking dictionaries

I never actually got this question from the Ong text, but from Jack Goody's "The Consequences of Literacy". You'll notice that Ong often cites Goody. The idea behind the fact that we are all walking dictionaries can be found throughout Ong, most notably on page 104 and 123ish, where he describes the modern vocabularies as "magna-vocabularies". There's so much information out there in the print culture that no longer are our means of communication aggregative, but actually very exclusionary. There is a lot of individual choice involved in reading--what you want to learn and read, and what you don't. As such, this can be an overwhelmingly alienating feeling because, as opposed to an oral culture where everyone in a particular milieu know the same things, the print culture read and relates only one the individual wants.

2. Off Sutter's Talk of Ramone Lull, name these terms for given to him: Motion, No Images, Non-Corporeal, Ladder, Tree.

Brandon's initial question was what are Thomas Acquinas's four rules of memory, and which ones were used by Lull. On Yates pg. 85, Acquinas's rules are: that the man trying to remember should dispose those things which he wishes to remember in a certain order, the second is that he should adhere to them with affection, the third is that he should reduce them to unusual similitudes, and the fourth is that he shuld repeat them with frequent meditation. Lull focused on this last rule of memory, in addition to introducing motion to memory. This is important because rather than the similitudes being stagnent, Lull uses the 9 attributes of God arranged in a circle (like an alethiometer) and moves the circle like you would a combinatorial lock. The stairs Lull uses to ascend to heaven and his tree to help memorize the abstractions. The stairs and the tree are images in and of themselves, but they are used to memorize not individual items, but Lulls memory schematisation in general. The memorization of abstractions, not similitudes, becomes visual.

3. Ong Chap. 6 - Triangle vs. Box (questions will go along these.... remember Fritag Triangular form as reference to Aristotle's Poetics vs. Mis-en-Abyme (into the abyss) Box within Box form of Orality)

This is probably one of my favorite questions that we could ask. The narratives of a literate culture form a triangle with a rising action, a climax, and a denoument (sp*). The box within a box tells the story of frames, infinite reflexivity, and endless allusion. Mis-en-abyme literally translates to "into the abyss", but, more generally, represents endless reflection and interplay between multiple narratives. It is a story within a story. For those of you who are unfamiliar or encountering this term for the first time, get to know it well--with all great literature you should find yourself in an abyss.

4. The Protestant Reformation = Printing Press

This is Snake-haired Kayla's question and its a great one. I just finished reading a book called "Wide as the Waters" by Benson Bobrick--very enlightening, with an overall point that the translation of the King James Bible from Latin (originally translated into Latin by St. Jerome) was an integral part in the founding of American Democracy. But, interestingly enough, why was the printing press so important to the Protestant Reformation? Because THE BOOK became THE WORD. No longer was faith placed in the church (as the clergy themselves couldn't hardly read Latin), but people bypassed unfrequented churches and went directly to the book and everyone was able to have a special relationship with God through text rather than use the corrupt clergy as the middleman to salvation. The Protestant Reformation essentially symbolizes faith in the book, in literacy.

5. Mandala - Squaring of the Circle

6. Democratic/Alphabet

7. Ong 142 - Gesang ist dasein. (Means "song is existence" in German)

8. Ong 130 - Finality and Closure (print)

This one is pretty self explanatory. When you put something on a page, it remains. When you say something orally, it vanishes, gone forever with the wind (but, after all, tomorrow is another day), lost as soon as its spoken. By being closed off, a work of print and text seems to be an entity unto intself, unable to interact with the reader or carry on an antagonistic, flyting tone. However, I do think there's is plenty of free play in text--websites are under construction, and by the time you read this I will probably have corrected myself a few dozen times. These corrections are allowed in text, but tend to be counter-productive in speech whereby the speaker loses credibility each time he corrects himself.

9. Yates 224 - The Memory System of ______ would require the memory of a divine man, the Magus. Bruno

In one of my previous blogs (2/24/09) I have a video of comedian Bill Hicks. Watch it and I think he really explains what happens to people like Bruno when they have come up with something great. No man is allowed to attain God-head. Let us recall the fall of Babel, where God banished man into different languages to confuse him because he aspired to be God. But I say go ahead and try...its not like you would cause one tenth of one tenth of one percent of the destruction and chaos God does.

10. What does alithiometer stand for? A Truth Measurer

Quite literally, the prefix A-LITH means an "unforgetting". You'll recall that lethe (lethal) means a forgetting. If you ever happen to be in Hades, stay away from this river or you'll become a zombie. If you read blogs by Phillip Pullman, who wrote The Golden Compass in which an Alithiometer (as well as a subtle knife and an amber spyglass) is used to find the truth about dust. I'd love to go into this for a while, but I can't, but, like I was saying, Pullman used Francis Yate's book as a primary inspiration for his epic fantasy. An unforgetting is somehow different than remembering in that you are undoing your forgetfullness, preening your angel wings, ready to take flight through experience--and to forge something special in the smithy of your own soul.

11. 7 Pillars of Solomon's House of Wisdom - Camillo (The 7 Planets of Yore)

After Lull I needed a break and haven't worked with Camillo yet, but this is on Yates page 138. Its all about astral science and the celestial world which I know nothing about...yet.

12. Iliad - "Such was the funeral rights of Hector, The Tamer of Horses"

I keep a horse on my patio. Not really, but it reminds me of this line, as well as the first and last lines of Richard III, which Wise Wandering Shannon knows well. Ask her, she'll recite some lines for you, she's really good at it.

13. Ong Chap. 4 - How many times was the alphabet invented? Once

14. What are the chances of something happening? 1 in 3 (The longer you live and the older you

get, you just realize that coincidences are always happening because you realize they do.)

15. What did Tai and Robert use for their memory systems? Their Bodies

Does anybody know Jesse Stolba, or anyone else with wonderful sleeves of tatoos and worded limbs? If my father would let me, I might get corporealities tattooed all over myself.

16. FW Article - Before writing their was speech, and before speech their was gesture.

The bottom line: reading preceeds writing.

17. Yates 188 - Lull and Cabala - System that arose from this

I believe the Cabal is all about word mysticism

18. FW Article - Hypertext & Portmanteau - (James Joyce and Cyberspace language)

Great question. A Portmanteau is a compartmentalized suitcase, or a word that means multiple things. If you ask Humpty Dumpty about it, he'll tell you that one word can have multiple meanings (or in Joyce's and the internet's case, dozens of meanings and links) because he "pays it extra" when it has to do a lot of work. Click here for some examples of portmanteaus as well as a link to Jabberwocky..."Twas brillig and the slithy toves did gyre and gimble in the wabe!"

19. Ancient Hebrew language was lacking what? Vowels. LTRTR NGLSH

21. Yates 203 - What is Bruno doing when he's said to be crazy and unrestrained? Bruno rushes out of convent/Divination of Man through memory

22. Ong 126 - Tristram Shandy's Silence - Blank Space

23. George Herbert's Poem "Easter Wings" (Hourglass Shape + Butterfly Wings) - Ong 126

We're talking about the exploitation of the typographic space. Blank lines on a page meaning silence, a new meaning given to the phrase "read between the lines". Click here to read Herbert's poem.

24. The most notorious book that nobody reads? FW

This is a fine question. Dr. Sexson asked if anyone has read FW and everybody raised their hands. Actually, from what I understand, no one "reads" FW, they sing it, they dance it. Dr. S said that all literature aspires towards FW, but we know that all art aspires to the condition of music. So, when we say "gesang est dasein", life and are are music. Nietzsche also said he would never worship a God who didn't dance. The words of FW dance of the page, and each time you reread a word it does a different dance. I can't wait to graduate so I can spend the better part of my unemployment singing FW. Like Brandon wants more question from Kane, I would have liked a few more from Sexson's article.

25. Myths are repository for practical knowledge.

Brandon felt compelled to do Kane justice. If I were Kane, I'd appreciat it. In an oral culture in which there were nothing but myths, the knowledge had to be practical or else it was thrown out and unneeded by the community. So there is no reason why an oral culture with mythologize something that was not of use to them.

26. The ability to hears colors? Synesthesia

Don't think you don't have the ability to hear colors, taste movement, or feel sound. I was once walking with a friend and he said, "I hear music." and I said, "You're not special, there's no other way to apprehend music." I love to be wrong.

1. Nietzsche says we are all walking dictionaries

I never actually got this question from the Ong text, but from Jack Goody's "The Consequences of Literacy". You'll notice that Ong often cites Goody. The idea behind the fact that we are all walking dictionaries can be found throughout Ong, most notably on page 104 and 123ish, where he describes the modern vocabularies as "magna-vocabularies". There's so much information out there in the print culture that no longer are our means of communication aggregative, but actually very exclusionary. There is a lot of individual choice involved in reading--what you want to learn and read, and what you don't. As such, this can be an overwhelmingly alienating feeling because, as opposed to an oral culture where everyone in a particular milieu know the same things, the print culture read and relates only one the individual wants.

2. Off Sutter's Talk of Ramone Lull, name these terms for given to him: Motion, No Images, Non-Corporeal, Ladder, Tree.

Brandon's initial question was what are Thomas Acquinas's four rules of memory, and which ones were used by Lull. On Yates pg. 85, Acquinas's rules are: that the man trying to remember should dispose those things which he wishes to remember in a certain order, the second is that he should adhere to them with affection, the third is that he should reduce them to unusual similitudes, and the fourth is that he shuld repeat them with frequent meditation. Lull focused on this last rule of memory, in addition to introducing motion to memory. This is important because rather than the similitudes being stagnent, Lull uses the 9 attributes of God arranged in a circle (like an alethiometer) and moves the circle like you would a combinatorial lock. The stairs Lull uses to ascend to heaven and his tree to help memorize the abstractions. The stairs and the tree are images in and of themselves, but they are used to memorize not individual items, but Lulls memory schematisation in general. The memorization of abstractions, not similitudes, becomes visual.

3. Ong Chap. 6 - Triangle vs. Box (questions will go along these.... remember Fritag Triangular form as reference to Aristotle's Poetics vs. Mis-en-Abyme (into the abyss) Box within Box form of Orality)

This is probably one of my favorite questions that we could ask. The narratives of a literate culture form a triangle with a rising action, a climax, and a denoument (sp*). The box within a box tells the story of frames, infinite reflexivity, and endless allusion. Mis-en-abyme literally translates to "into the abyss", but, more generally, represents endless reflection and interplay between multiple narratives. It is a story within a story. For those of you who are unfamiliar or encountering this term for the first time, get to know it well--with all great literature you should find yourself in an abyss.

4. The Protestant Reformation = Printing Press

This is Snake-haired Kayla's question and its a great one. I just finished reading a book called "Wide as the Waters" by Benson Bobrick--very enlightening, with an overall point that the translation of the King James Bible from Latin (originally translated into Latin by St. Jerome) was an integral part in the founding of American Democracy. But, interestingly enough, why was the printing press so important to the Protestant Reformation? Because THE BOOK became THE WORD. No longer was faith placed in the church (as the clergy themselves couldn't hardly read Latin), but people bypassed unfrequented churches and went directly to the book and everyone was able to have a special relationship with God through text rather than use the corrupt clergy as the middleman to salvation. The Protestant Reformation essentially symbolizes faith in the book, in literacy.

5. Mandala - Squaring of the Circle

6. Democratic/Alphabet

7. Ong 142 - Gesang ist dasein. (Means "song is existence" in German)

8. Ong 130 - Finality and Closure (print)

This one is pretty self explanatory. When you put something on a page, it remains. When you say something orally, it vanishes, gone forever with the wind (but, after all, tomorrow is another day), lost as soon as its spoken. By being closed off, a work of print and text seems to be an entity unto intself, unable to interact with the reader or carry on an antagonistic, flyting tone. However, I do think there's is plenty of free play in text--websites are under construction, and by the time you read this I will probably have corrected myself a few dozen times. These corrections are allowed in text, but tend to be counter-productive in speech whereby the speaker loses credibility each time he corrects himself.

9. Yates 224 - The Memory System of ______ would require the memory of a divine man, the Magus. Bruno

In one of my previous blogs (2/24/09) I have a video of comedian Bill Hicks. Watch it and I think he really explains what happens to people like Bruno when they have come up with something great. No man is allowed to attain God-head. Let us recall the fall of Babel, where God banished man into different languages to confuse him because he aspired to be God. But I say go ahead and try...its not like you would cause one tenth of one tenth of one percent of the destruction and chaos God does.

10. What does alithiometer stand for? A Truth Measurer

Quite literally, the prefix A-LITH means an "unforgetting". You'll recall that lethe (lethal) means a forgetting. If you ever happen to be in Hades, stay away from this river or you'll become a zombie. If you read blogs by Phillip Pullman, who wrote The Golden Compass in which an Alithiometer (as well as a subtle knife and an amber spyglass) is used to find the truth about dust. I'd love to go into this for a while, but I can't, but, like I was saying, Pullman used Francis Yate's book as a primary inspiration for his epic fantasy. An unforgetting is somehow different than remembering in that you are undoing your forgetfullness, preening your angel wings, ready to take flight through experience--and to forge something special in the smithy of your own soul.

11. 7 Pillars of Solomon's House of Wisdom - Camillo (The 7 Planets of Yore)

After Lull I needed a break and haven't worked with Camillo yet, but this is on Yates page 138. Its all about astral science and the celestial world which I know nothing about...yet.

12. Iliad - "Such was the funeral rights of Hector, The Tamer of Horses"

I keep a horse on my patio. Not really, but it reminds me of this line, as well as the first and last lines of Richard III, which Wise Wandering Shannon knows well. Ask her, she'll recite some lines for you, she's really good at it.

13. Ong Chap. 4 - How many times was the alphabet invented? Once

14. What are the chances of something happening? 1 in 3 (The longer you live and the older you

get, you just realize that coincidences are always happening because you realize they do.)

15. What did Tai and Robert use for their memory systems? Their Bodies

Does anybody know Jesse Stolba, or anyone else with wonderful sleeves of tatoos and worded limbs? If my father would let me, I might get corporealities tattooed all over myself.

16. FW Article - Before writing their was speech, and before speech their was gesture.

The bottom line: reading preceeds writing.

17. Yates 188 - Lull and Cabala - System that arose from this

I believe the Cabal is all about word mysticism

18. FW Article - Hypertext & Portmanteau - (James Joyce and Cyberspace language)

Great question. A Portmanteau is a compartmentalized suitcase, or a word that means multiple things. If you ask Humpty Dumpty about it, he'll tell you that one word can have multiple meanings (or in Joyce's and the internet's case, dozens of meanings and links) because he "pays it extra" when it has to do a lot of work. Click here for some examples of portmanteaus as well as a link to Jabberwocky..."Twas brillig and the slithy toves did gyre and gimble in the wabe!"

19. Ancient Hebrew language was lacking what? Vowels. LTRTR NGLSH

21. Yates 203 - What is Bruno doing when he's said to be crazy and unrestrained? Bruno rushes out of convent/Divination of Man through memory

22. Ong 126 - Tristram Shandy's Silence - Blank Space

23. George Herbert's Poem "Easter Wings" (Hourglass Shape + Butterfly Wings) - Ong 126

We're talking about the exploitation of the typographic space. Blank lines on a page meaning silence, a new meaning given to the phrase "read between the lines". Click here to read Herbert's poem.

24. The most notorious book that nobody reads? FW

This is a fine question. Dr. Sexson asked if anyone has read FW and everybody raised their hands. Actually, from what I understand, no one "reads" FW, they sing it, they dance it. Dr. S said that all literature aspires towards FW, but we know that all art aspires to the condition of music. So, when we say "gesang est dasein", life and are are music. Nietzsche also said he would never worship a God who didn't dance. The words of FW dance of the page, and each time you reread a word it does a different dance. I can't wait to graduate so I can spend the better part of my unemployment singing FW. Like Brandon wants more question from Kane, I would have liked a few more from Sexson's article.

25. Myths are repository for practical knowledge.

Brandon felt compelled to do Kane justice. If I were Kane, I'd appreciat it. In an oral culture in which there were nothing but myths, the knowledge had to be practical or else it was thrown out and unneeded by the community. So there is no reason why an oral culture with mythologize something that was not of use to them.

26. The ability to hears colors? Synesthesia

Don't think you don't have the ability to hear colors, taste movement, or feel sound. I was once walking with a friend and he said, "I hear music." and I said, "You're not special, there's no other way to apprehend music." I love to be wrong.

Sunday, April 5, 2009

Grapholects

Today I randomly chose a page in Ong to explicate for my paper. There's just too much to be able to decide on my own, so I let Fortuna decide. I put my finger on page 104 and I'm very happy with it. I was telling Dr. Sexson a few days ago that with the internet it is impossible to get a good deal or haggle with anyone because people know too much. Back in the day (a day I wasn't there for, but my dad tells me about it) you could get a deal because people didn't know as much. My dad says, "Some people know the price of everything and the value of nothing". So continuing with this idea, Ong talks about how huge the modern grapholect is. Like Nietzche says, were all walking dictionaries with magna-vocabularies, and, as such, according to Jack Goody, this leads to an overwhelming sense or alienation because we can pick and choose what we want to know. In an oral culture it was all right there. Everybody knew what everyone else knew, there was no superfluous material or esoteric material. But it was also aggregative, and in today's literate world, some people know some things while other people know different things. Ong even mentions that the modern day giant sized grapholect has led to the rise of "grammar Nazis" because where grapholects exist, "correct grammar and usage are popularly interpreted as the grammar and usage of the grapholect itself to the exclusion of the grammar and usage of other dialects. So...that's what I'll write my paper on. I'd love to write it about electricity, but maybe I'll save that for my Ph.D dissertation.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)